This post is a continuation of parts one and two, discussing TREC’s Study Paper on Governance and Administration

In the first post, Theophilus, I discussed TREC’s (the Taskforce for Re-imagining the Church’s) suggested reforms in general, and pointed out that their financial recommendation to cut the diocesan asking to the biblical tithe (10%) could cost DFMS as much as $27 million in revenue. In the second post, I talked about their suggested reforms to General Convention and estimated that they might save around $400,000 in all. In this post, I will discuss the rest of their suggestions and count up where we are, money-wise.

The Office of Presiding Bishop

What are the absolutely vital tasks that we need a Presiding Bishop to do? What are the other tasks that have fallen to the Presiding Bishop over the years that could be accomplished in other ways? What are the most appropriate ways to do these other things?

The Presiding Bishop, as I have argued before, fills three roles in our church:

- Presiding Officer of the House of Bishops. This was the original office. As presiding officer, the PB has big responsibilities in governance, including General Convention, Executive Council, and so forth, and also properly handles responsibilities such as pastoral development of bishops and bishop disciplinary matters. This role includes a lot of travel within TEC.

- Primate. The PB is the spokesperson for the church to the world, including representing us in the councils of the Anglican Communion and ecumenical affairs, advocating for justice issues, speaking for the church in times of national crisis, etc. This role includes a great deal of U.S. and international travel. This function was not contemplated in the original job description of the PB, but we need this kind of public leader. If we didn’t have one, we would invent one.

- CEO and Head of Staff. The original office of PB certainly never contemplated that the PB would have a staff, other than perhaps an administrative assistant. But the church-wide staff has grown to the point that it would be impossible for a PB to do her other two roles and keep track of the staff as well. Therefore, staff oversight is mostly delegated to a Chief Operating Officer who functions, effectively, as the CEO, and is accountable only to the PB.

The first role is the original office, and it is a vital one. The second role was added much later, as it became more and more necessary to have a bishop who would act as the church’s face to the world. I think it is vital for the PB to fill these two roles, and frankly, filling these two roles is all any one human being can do.

I do not think it is vital for the PB to fill the third role. In fact, I think it is inappropriate – in the sense that if the PB is CEO and head of staff, it means the staff is accountable only to one person who was elected by only one house of General Convention and who really doesn’t have time to oversee them because of his/her other two vital roles. Unless General Convention is willing to bring a PB up on charges (which I hope will not happen in my lifetime), Convention is required to fund offices that it has no ability to hold accountable.

In addition, PBs are not (or should not be) elected for their administrative abilities. They are (or should be) elected because they are inspiring leaders and speakers, and we want them to be our spokespersons to the world. Let’s turn them loose to do what they were elected to do, and let capable administrators run the Church Center (wherever it is located), with appropriate oversight from the church’s elected representatives.

The PB does, of course, need staff in her own office to help her fulfill her duties. That would include governance, communication, and disciplinary duties, as well as Anglican Communion liaisons and ecumenical officers, in my opinion. It makes sense for those functions to be handled through the Primate’s office, since she is our spokesperson to the world.

But I believe that the bulk of the DFMS staff should report to a different person who is accountable to both houses of Convention. Staff who report to different officers can still all be paid by DFMS and be subject to DFMS human resources, employment, and travel policies.

Therefore, as far I am concerned, Alternative II in the TREC paper moves in completely the wrong direction, centralizing even more duties in the hands of the PB than she already has, and making the job even more impossible than it already is. Alternative III is better, but seems to envision the PB taking on too small a church-wide role, possibly keeping her diocesan see (what this accomplishes is unclear). Therefore, I think Alternative I is the best choice: keeping a healthy view of the PB’s leadership, while allowing for Council oversight (not micro-management) of the head of staff (“CEO” is a poor name for this position). Alternative I also seems to be the one that TREC has thought hardest about, judging from the verbiage devoted to the three alternatives.

Alternatives I and II don’t save us any money, but they don’t cost us any money either. We already pay both a PB and a Chief Operating Officer. Alternative III will cost us money, because the poor diocese that is saddled with a PB as its diocesan bishop will need a subsidy to call a suffragan bishop. Let’s say Alternative III costs us $500,000 per triennium.

Executive Council

What is the Executive Council? What do they need to do that no one else can do, how many people does it take to do those things, and where do they fit within the power structures of the church?

Well, full disclosure – I serve on Executive Council (that’s me in the photo, in the green jacket just over Silvestre Romero’s left shoulder). I was elected by Convention in 2012, and my term goes until 2018 – argghh, that seems like a long time!

Well, full disclosure – I serve on Executive Council (that’s me in the photo, in the green jacket just over Silvestre Romero’s left shoulder). I was elected by Convention in 2012, and my term goes until 2018 – argghh, that seems like a long time!

Executive Council, as TREC points out, has two roles. (1) It is the designated body to carry out Convention’s policies while Convention is not in session. And (2) it is the legal Board of Directors of DFMS / The Episcopal Church. These are two, not-always-congruent roles.

Executive Council IS a large group – it is hard for a group of 40 people to act as a board of directors. However, most of Council’s work happens in committee (just as is the case with General Convention). Could a group of 21 accomplish the work of Council? Probably, if all 21 are good, active representatives, and not blowhards or inactives. Is it worth a try? Sure, if we think it will really accomplish something. The money spent by Council in meetings is not that much in the context of an overall budget in excess of $111 million (Council meetings cost less than $750,000 for the triennium, less than 1% of our budget, and this presumably includes the cost of having a significant staff contingent at each meeting), but if the church wants to reduce the size of Council, I won’t protest as long as there are other provisions to accomplish Council’s work (and note that Council’s work may increase under the proposals).

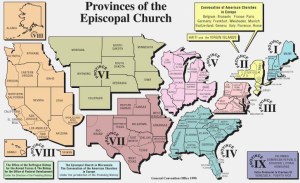

I think it would make sense for the remaining CCABs, and for task forces established by Convention, to report to Council, and for Council to have authority to establish other task forces as necessary, as TREC proposes. Note that I have already recommended that we do away with the provincial structure, so I think TREC should re-think how Council is elected.

The good thing about Council is that it is, in fact, a representative group. We are elected by the Church to be leaders. Those Council elections are important, especially if, as I believe should happen, these representative leaders are given more responsibility to oversee (not micro-manage) the work of the head of staff. I do believe that Council, as an elected, representative group, is the best-situated group to do this oversight work on behalf of the whole Church.

Future Council members: come prepared to lead. Come with an agenda for action. Don’t accept the role of routine rubber-stamper or passive accepter of the status quo. The church needs more than that from us. It needs us to be leaders, catalysts for change, and innovators.

The Money Scorecard

The budget for Council meetings is approximately $750,000 per triennium. Let’s say we can save $300,000 under this proposal – a generous estimate.

Staff

What is the staff for? What things do we need to pay people to do? What things can DFMS do that no one else can do? And by the way, what kind of functions should a church-wide headquarters building support?

It is hard for me to believe that TREC issued a report on “Governance and Administration” and barely touched the question of what the staff should be doing. The report’s main discussion of staff was about who should supervise them.

Yet TEC’s 2013-15 triennial budget shows 12% spent on Governance, including only $2 million on General Convention, which takes up the bulk of the TREC report, and 78% on everything else, including 30% on Administration. This 78% of our expenditures wasn’t worth discussing? Governance has to bear the full weight of our restructuring efforts? Folks, we’re not going to get down to a 10% tithe without addressing Administration, staff roles and responsibilities, and what kind of headquarters building we need.

So what do we need a church-wide staff to accomplish? Do we want program staff? Do we want all program functions to devolve to voluntary networks instead? What do we think is unnecessary?

Note that TREC’s proposals listed above have barely affected the cost of our church-wide structure at all, maybe saving $1 million at most (less than one percent of our DFMS budget). If we’re going to get the church-wide assessment down to the biblical tithe (which I think is a terrific number! but remember, that is as much as a $27 million reduction!), the staff plus other projects NOT EVEN MENTIONED IN THE TREC REPORT are going to bear the brunt of the reduction.

If they don’t want to talk about it, I will.

I think we can divide our budget into:

(1) things DFMS can do that need to be done and no one else can do;

(2) things DFMS can do that are nice to have done and no one else can do; and

(3) things DFMS can do that are nice to have done but other people can do.

If we are going to cut the budget by $22 to $27 million, we are going to have to decide something like the following: The church-wide budget needs to support (1), should support (2) to the extent we have the funds, and should not support (3), perhaps not cutting these amounts immediately, but working to reduce them over time.

(1) Things DFMS Can Do That Need to be Done and No One Else Can Do

- Functions of governance – PB office, PHoD office, General Convention, CCABs, Secretary of Convention, Title IV work, etc. (Discussed in part two.; current budget around $13 million)

- Ecumenical, interfaith, and Anglican Communion work. (Current budget $8 million)

- Federal Ministries. (Current budget $1.6 million)

- Communications, including marketing strategy for The Episcopal Church (no postcards, please). (Current budget $9.1 million)

- Finance, human resources, legal, and information technology. (Current budget $19 million, not counting debt service or facilities maintenance.)

- Maintenance of some sort of headquarters location. It, ahem, doesn’t have to be in Manhattan. (Current budget includes $8 million of debt service and $7 million of facilities maintenance, offset by $5 million of rental income, total $10 million.)

These are necessary functions and we need to accomplish them at the church-wide level – not to say that there isn’t room for cutting budget funding in these areas. Maybe we could bring the litigation to an end, someday? Do we really need such a costly administrative staff? Maybe we could get rid of those debts and get a cheaper headquarters location? The 2012 General Convention voted to move the Church Center away from its current location in Manhattan, an action I supported. Of course, that action has run into resistance from the Church Center itself. Executive Council continues to work on this issue, and we are making some progress, but the real issue won’t be solved until we know what kind of staff we need and are able to fund.

These are necessary functions and we need to accomplish them at the church-wide level – not to say that there isn’t room for cutting budget funding in these areas. Maybe we could bring the litigation to an end, someday? Do we really need such a costly administrative staff? Maybe we could get rid of those debts and get a cheaper headquarters location? The 2012 General Convention voted to move the Church Center away from its current location in Manhattan, an action I supported. Of course, that action has run into resistance from the Church Center itself. Executive Council continues to work on this issue, and we are making some progress, but the real issue won’t be solved until we know what kind of staff we need and are able to fund.

Note that the “Administration” line in our church-wide budget is over 30% of our spending for the triennium – a cool $34 million. TREC hasn’t even glanced at these expenditures.

(2) Things DFMS Can Do That are Nice and No One Else Can Do

- Most of our program offices, from Christian Formation to Ethnic Ministries, fall into this category. Most ministry in these areas happens at the local level, but church-wide coordination and support for learning and networking is certainly valuable. For instance, with proper funding, some great work could be done by the Office for Hispanic/Latino Ministries in developing lay and ordained leadership training for church planting nationwide. (Current budgets: Formation & Vocation $3 million; Congregational Development $4 million; Ethnic Ministries $4 million)

- Sending of missionaries into other parts of the world. (Current budget $3.6 million.)

- Social justice advocacy, including the Office of Government Relations. (Current budget: $3.3 million)

I support all of these efforts, but we need to look carefully at how much we can actually afford in each area. Especially if we’re going to reduce our diocesan asking to the biblical tithe, as TREC recommends. TREC: which of these functions would you like to get rid of? Reducing our asking from 19% to 10%, a $27 million reduction, is going to require some painful inroads into this category, I am afraid.

(3) Things DFMS Can Do That Are Nice and Other People Can Do

- Marks of Mission Grants – I really like these grants, especially Mission Enterprise Zones, which I think could be truly transformative across the church. But the fact is, these grants take money given by the dioceses and give the money back to the dioceses. They are redistribution schemes – from committed and/or wealthy dioceses to dioceses with good ideas. Do we want to continue sustaining redistribution schemes? If so, we are not going to be able to get our asking down to 10%. Marks of Mission grants totaled $5.5 million in the current triennium. When I say “other people can do” these things, I mean, maybe we will have to decide to leave this money in the dioceses we got it from, to support mission in those dioceses.

- Grants for Province IX dioceses, non-self-sustaining dioceses within the US and Europe, and Anglican Communion partners – we spend huge amounts on these ($10 million within TEC, $2.7 million on grants and covenants within the Anglican Communion). I don’t think we can just drop these folks cold turkey. Can we work these partners toward sustainability over time? This project is already underway in Province IX.

- Grants for other supported entities, such as Historically Black Episcopal Colleges (current budget $1.8 million).

- CCABs: most work of the CCABs can be accomplished by informal networks and elected representatives. (Current budget $730,000)

- Support for provinces – I think we can eliminate the provincial structure. (Current budget $300,000; most savings will come at the diocesan level.)

- General Board of Examining Chaplains – if we need this function, it can support itself by increased user fees.

And so on – this category requires careful analysis. Are we willing to pull back on all these commitments?

You may disagree with my classifications, and whether we should be funding categories 1, 2, or 3 as the highest priority. Terrific – let’s have the discussion. TREC hasn’t had it, as far as I can tell.

The point is: we need to decide what we want our church-wide staff and budget to accomplish. Until we have decided this, simply suggesting new asking percentages like the biblical tithe is not going to fix anything. TREC: please tell us what you think our church-wide structures should be doing. Your almost-exclusive focus on governance (which, by the way, doesn’t really end up saving much money at the church-wide level) allows the majority of our expenditures to escape notice altogether. What about the other category in your paper’s title – Administration?

Back to the main question: what do we want to actually accomplish at the church-wide level? Until we have answered this question, we are just wandering through the weeds, speculating on how many deputies we should have per diocese, a fairly minor question in the overall financial picture.

The Money Scorecard

TREC Proposals: no effect. No attention paid to this category whatsoever.

Conclusion

TREC makes an utterly unrealistic recommendation to reduce the asking to the biblical tithe. Oh, it can be done, but not based on the reforms they are suggesting, which might save $1 million at best. Unless TREC does some real work to find another $26 million of cuts, it would fall to the heroic efforts of PB&F to find those cuts at the last minute, should such a proposal pass the next General Convention. Which would make PB&F the ACTUAL Taskforce to Restructure the Church, the same as it was in 2009, no matter what it is called. If TREC doesn’t do this work, then I think it is irresponsible of them to suggest such a reduction and leave the burden to someone else.

Let me reiterate: I am completely in support of reducing our diocesan asking. I think it is far too high, and I think we need to look carefully at what we are asking our church-wide structures to do so that we can make significant reductions in the asking. But reducing the budget by $27 million would end up being, effectively, the true restructuring of our church. Is that what we want – restructuring by budget cuts on the second to last day of Convention? Or do we want TREC to take a realistic, comprehensive, and responsible look at what they are suggesting that we do?

In the end, it’s all about mission: what should The Episcopal Church be doing? How should we be reaching out to new folks with the life-transforming love of Christ? How should we be changing the world? How much of this work can the church-wide structure empower and support? And what should we NOT be doing?