Scriptures for this Sunday are here.

Listen to this sermon here:

In the Episcopal calendar of saints last week, we remembered Janani Luwum. Born in Uganda in 1922, he was a lifelong Anglican, educated in England. He returned to Uganda and rose to become archbishop of Uganda in 1974. It was a position where he could either collude with the dictator Idi Amin, or risk his life by opposing his brutal regime. He chose the second course, becoming a leading critic of excesses of regime. In 1976, when government troops attacked and ransacked a university, Luwum chaired a group of religious leaders that wrote a memo of protest.

In 1977, Luwum and other leaders were summoned to the presidential palace and accused of treason. The other leaders were asked to leave, but Luwum was told to remain behind. As his companions left, Luwum told them, “They are going to kill me. I am not afraid.” He was never seen alive again, and the next day his family told he was killed in a car crash. At his funeral, his body still missing, the crowd chanted, “He is not here! He is risen!” Several weeks later, his body was finally released to his family. They opened the casket and saw that he was riddled with bullets.

According to witnesses, he was probably personally shot by Idi Amin. He’s one of the most celebrated 20th century Anglican martyrs, with his statue at Westminster Abbey among the martyrs of the church.

As I listened to his story last Wednesday in evening prayer, I was struck with not only the courage he displayed in opposing the regime, but the incredible contrast his life poses with mine, and with most of ours. For us, being Christian requires no particular courage. It may even score us points in being more upstanding, better connected in society than others – after all, political candidates in US score big points for being Christians. Because Christians are dominant in the US, it’s easy for us to have lukewarm faith, to take no chances, to treat our faith as incidental to our lives, something to fit in after we’ve done everything else that is important to us. We can take Jesus for granted, we can assume he will be there to comfort us when we are in trouble, we can live our life taking no risks for the gospel. The life of a martyr, who lives with courage, who subjects himself to persecution and death for the sake of Jesus and the ones Jesus loves, is almost startling to us. We know long-ago Christians risked everything for their faith. It’s much easier to forget that Christians are still doing these things today. And even easier to forget that Jesus still calls us to risky, courageous living for the sake of our faith.

Take a look at the gospel today for an example of risky courage. It’s an odd little story, full of foxes and hens and little chicks being gathered up under mama’s wings. But it’s also a story of courage and daring. So often today we see love as an easy, pleasant, feel-good thing. But love for Jesus is not a simple sentimental emotion, a way of looking kind and nice to his neighbors, a way of fitting in and being socially acceptable, which is what love too often means for Americans, with our romantic movies and Valentines.

Love for Jesus isn’t about Valentines and chocolates – love for Jesus is risky, it’s dangerous, it is courageous, it’s frightening, it requires him to be vulnerable.

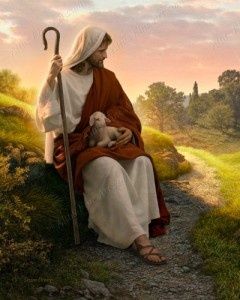

We could easily see this little hen Jesus compares himself to as a sweet, domestic, affectionate little creature – and that’s true, but it’s not complete. Because this motherly little hen is using her body to shield her chicks from the fox Herod, who is a stand-in for all the corrupt powers of the world that oppress people. Bishop NT Wright points to a well-known farmyard image: of a barnyard after a fire, with a blackened hen dead in the fire, with her wings spread out, still sheltering a brood of living chicks, protected by her body. The motherly love of that hen takes form of sacrificing herself to save her children.

Jesus knows perfectly well that’s exactly what will be required of him. He knows the people in power want to kill him. He’s on his way to Jerusalem, where he will die. And he’s determined to do exactly that, for love. When helpful Pharisees try to warn him off confronting the powers in Jerusalem, the seat of power in his country, because Herod wants to kill him, Jesus responds not with fear of the painful death he knows is awaiting him, but with tenderness for the very people who are putting him in danger. “Jerusalem, Jerusalem,” he laments. “The city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it! How often have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing!”

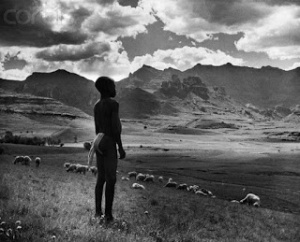

Indeed, many prophets have been ill-treated in Jerusalem, as the Bible tells us. And we should not make the mistake of interpreting this lament as anti-Jewish or an indictment of Jerusalem alone, because Jesus and all the disciples were Jewish. What Jesus is talking about here is the universal human tendency for the powerful to protect themselves at the expense of others, to do anything, including murder, to shore up their strength. He is speaking in the role of the prophet. Prophets are those who, as the Jewish scholar Abraham Joshua Heschel said, “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.”

Comforting the afflicted is what Jesus is doing with his healing ministry “today and tomorrow” – that is, on an everyday basis. But on the third day, he finishes his work, moving to Jerusalem, the seat of power, to afflict the comfortable – and the powerful people in Jerusalem, like in any society, will not respond well to being afflicted – they will kill him.

But his death will have a purpose: his reference to the “third day” makes it clear. His death will open the way to eternal life; it will defeat the power of evil and death; and it will show us the ultimate way of self-giving love.

Love is more than a cozy, comfortable emotion. Jesus’ love for his city Jerusalem, and for any city or community or nation where people struggle for power and control, takes the form of courageous tenderness that puts himself at risk, where he interjects himself into places of danger out of love. And his willingness to risk himself will mean salvation for those he loves.

Christian love means that we might lose everything, but it means that we, and the world, might gain everything too. The world is better for the witness of Jawani Luwum, who gave everything for love; and the world has salvation because Jesus was willing to spread his wings over us and protect us – which is courageous, daring, risk-taking, self-giving love.

So how, in our comfortable world where we are at no risk of being persecuted for our faith, are we to exercise such daring, courageous, self-giving love? Interestingly, the social work researcher Brene Brown has done a lot of work on this question. If you’ve seen her famous TED talk, you know that she became interested in how people live what she called “whole-hearted lives.” She’s Episcopalian and got the term from our confession – we have not loved you with our whole heart.

She discovered that people who experience joy in life weren’t different from others because they had fewer problems, or more money, or better health, or a more comfortable upbringing, or more education, or anything else. What they had was the courage to risk being vulnerable. Because love is inherently risky. Any connection with another human being, she found, requires us to open up and let that other person see us as we really are – which means that in order to love, we have to forget about being perfect, we have to dare to be vulnerable.

True human love and care for another person requires accepting who we are and allowing other people to accept that too. And who we are is imperfect struggling people. And the people who were willing to be vulnerable, she found, were the ones who knew how to love, who lived with conviction, who committed themselves to others. She points out that we so often see “courage” as a sort of iron shell, where a person has no vulnerability at all. When in fact “courage” is a willingness to give your heart to something even though it will almost certainly hurt. As I discovered when my first child was born, the choice to become a parent is a choice to let part of your heart go walking around outside your body from then on.

Any love is like that. Any love requires vulnerability. Any love is risky. Any love takes courage. But love – risky, dangerous, courageous love – lets us live wholehearted lives.

I think in that truth is the key to the Christian life. Because the truth at the heart of our faith is that we are imperfect people. We make mistakes, we ask for forgiveness, we know we cannot save ourselves, we allow God to save us.

We have not loved you with our whole heart, we have not loved our neighbor as ourselves. We are truly sorry, and we humbly repent.

In our recognition of who we truly are, in our admission before God and before others that we have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God, we gain the ability to live with courage. To open ourselves to connection with God, to let God’s love live in us. To share that love with others.

Because courageous martyrdom like Janani Luwum’s is not the only kind. In the church those who have died for their faith are “red martyrs”.

But there’s another kind – “white martyrs.” Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby said this week that white martyrs are those whose lives are so utterly dedicated to Christ, whose life is so surrendered, that they speak of Christ in everything they do or say. Which is where I think we comfortable, religiously free Americans can give real witness to our faith, can live with courage and love for this world. Because our society may be perfectly happy for us to call ourselves Christian, that may even score us some points, but for us to live like Christ, to witness to him in everything we do or say, to have the courage to speak our faith and speak out our love and care for this world and take action to make that love real; to challenge those who hurt others, to oppose the powers of poverty, crime, racism, oppression, to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable: these things take courage. The courage to risk our reputation for our love. But that kind of courage is worth it.

Because in our life and in our death, in our love and in our courage, like Jesus, we glorify God. And that is the goal of the Christian life.